On Oct. 20, 13 days after Hamas’ brutal surprise attack on Israel, the content creator Megan B. Rice took to TikTok to record an emotional video.

“No, but can we talk about the Palestinian faith real quick?” Rice posted on TikTok on Oct. 20. “Because it’s unlike any I have ever seen. I have quite literally seen videos of people who have lost everything, even their children, and they are holding their dead children in their arms and still thanking God, still asking God to take care of their children from there.”

In the nearly two weeks since Oct. 7, more than 4,000 Palestinians — many of them children — had been killed by Israel’s ceaseless airstrikes. Facing a shortage of fuel, food, water and electricity, the entire Gaza strip was teetering on the brink of what Human Rights Watch calls “a humanitarian catastrophe.”

That catastrophe has galvanized many on TikTok, like Rice, whose videos previously revolved around updates and observations about her personal life, pop culture and books, to publicly decry Israel’s treatment of Palestinians.

Her video received more than 1.1 million views, and hundreds of TikTok users flocked to the comments to share their agreement. “Facts! I’m not even Muslim and the unity of the Ummah and faith in Allah is beautiful. I can only hope to have an ounce of that one day,” one user posted. “This! I’m in no way a religious person now but seeing their love and faith for Allah brings me to tears. I wish I had that in a religion,” another echoed.

The next day, on Oct. 21, Rice decided to listen to an audiobook of the Quran for the first time. She posted her initial observations about it in a TikTok, saying she was “enjoying the read” so far, and received hundreds of comments, many from followers purporting to be Muslim offering her support and encouragement to continue her exploration. Two days later, Rice announced she was starting a virtual World Religion Book Club for anyone interested in reading and talking about religious texts, primarily the Quran. Garnering even more engagement from her audience, less than three weeks after that, on Nov. 11, Rice took her shahada — the Muslim declaration of faith and an official gesture of conversion to Islam — on TikTok Live, in front of an audience of more than 8,000 people. In less than a month, Rice had gone from irreligious to a devout Muslim, her conversion sparked specifically by the ongoing events in Palestine. During the same period, her followers more than tripled, from 227,400 to 832,100. (Rice now has nearly 922,000 followers).

Rice, who has said she previously identified as having “no religion,” is just one example of a larger trend on the social video platform: Thousands of American Christians and Jews, inspired by the Palestinians’ strength of faith in the face of overwhelming violence and hardship, say they are reading about Islam for the first time to understand the origins of that faith. Some are evidently so moved by their discovery that they’ve made the life-altering decision to convert to Islam, bringing them a host of new admirers and, inevitably, detractors who criticize them for perceived insincerity or opportunism, valuing clicks over true piety. Internet celebrity is even more fickle and fleeting than the offline variety. Although social media is designed to be a platform for infinite experimentation with personae and identity, abiding faith is fundamentally at odds with virality. In the case of these TikTok converts, experts fear, once Israel’s war in Gaza is finished, so too will their commitment – and what will that say about what it means to be a Muslim in modern America?

In the days since the Oct. 7 attack, searches on Google for the Quran spiked, and have maintained those highs; on TikTok, where the topic “Quran Book Club” has more than 15.8 billion views, many began reading the Quran for the first time. Some of those people, like Rice, and the formerly Jewish creator @JackJackWilds, are even converting to Islam. New Lines has spoken to several of them about their experiences. Clarke Jones (a pseudonym), is a 30-year-old American woman raised in a very conservative sect of the Church of Christ. She also converted to Islam not long after seeing Rice take her shahada. After leaving the church when she became an adult, Jones spent 12 years as an atheist before converting to Islam last month. She said that before Oct. 7, she didn’t know much about the plight of the Palestinian people, but after seeing their strength of faith, it drew her to reconsider her own religious values. “I would say that Palestine itself didn’t make me convert,” she told New Lines. “But Palestine made me pick up the Quran. I originally picked up the Quran for education and solidarity and when I read it, it was describing what I already felt and what I already believe.”

Others on TikTok have told of a similar trajectory to conversion. Jamie Rosario, a 30-year-old product owner in Tampa, Florida, said she had always been a believer in something, dabbling in astrology and mysticism and the planets, but had never known exactly what it was she believed. When she started seeing videos of the depth of faith displayed by Palestinians, and watched Rice as she began parsing the Quran on TikTok, she was inspired to read the Quran herself. A few weeks later, she converted.“Being a child growing up in New York City after 9/11 and seeing how Islamophobia developed from that, the Quran was entirely a mystery to me,” Rosario said. “I realized I was always just taking what I knew about it from Western media. So I decided to read it just to combat the propaganda and conditioning in myself that was making me have these preconceived notions about Islam … In the last 3 weeks, since I reverted, I’ve been keeping up with my daily prayers and I feel so much peace,” Rosario told New Lines. “Coming from a divorce, having sold my house, even the friends I had five years ago — it’s all a blank slate for me right now and the Quran and Islam and the community I’ve found is one of the things that has brought me a sense of hope and optimism. I’m returning back to who I was always meant to be.”

The wave of conversions like Rosario’s is reminiscent of anecdotes about an uptick in conversion to Islam in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, particularly among women. Though unlike now, when solidarity with the suffering of the people of Gaza seems to be leading such conversions, back then any such trend was not a show of solidarity for the terrorists, but because Islam had become a daily topic of interrogation and examination in the public sphere, with seemingly anyone from prime-time news presenters to Hollywood producers weighing in.

Rice’s World Religion Book Club, started “to directly combat Islamophobia, prejudice, discrimination, hate toward religion, toward ethnicities, toward nationalities,” lives on a Discord server, which hosts events and online meetings, like interfaith discussions on religious topics and stories from the Torah, the Bible and the Quran. There are also plenty of beginner classes for those interested in converting to Islam, taught by experienced Muslims, like “Tajweed for Beginners” and “Getting to Know Allah.” In this way, the book club is hoping to help challenge the common Western misconception of Islam as an inherently violent religion.

Dr. Mohammed Hafez, a Palestinian-American professor of politics in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School, told New Lines he believes there are two specific dynamics that are leading to the spate of TikTok conversions: a search for personal identity, and a connection to Muslim and Palestinian networks. “Oftentimes people who convert in the context of these political crises are individuals who are unanchored in a religious view, they’re searching for meaning,” he said. “In this case what’s happening is you have people who are searching for a new identity but at the same time they are connected to Palestinians and Muslims who are activating around Gaza, and then they start to link the two together. So it’s those two interacting — the quest for identity, and the connection to Palestinian Muslims — that is leading to this conversion in this time.”

Jones said that she believes a big part of the phenomenon of recent conversions is “so many of us in the West realizing how deeply we’ve been lied to.”

“I was in first grade when 9/11 happened,” she told New Lines. “I very much grew up in a culture of Islamophobia and it has completely shaken me, the things that I was always taught that I know now are not true. It has me questioning everything.”

Rosario agrees, and told New Lines that this moment is just as much about politics and rejecting capitalism as it is about religion. “I think we’re all realizing that we’ve been too attached to celebrity culture and overconsumption and it’s important for us to have this moment — whether it’s leading you to Islam or leading you to be a more present and aware person — it’s important to recognize that some of these things that we thought matter truly don’t.”

Whatever is motivating some social media influencers to make a public display of conversion to Islam — and however authentic such conversions may be — the trend goes beyond a purported crisis of personal faith. It comes intertwined with politics, war and propaganda. This became especially evident when Osama bin Laden’s “Letter to America” went viral on TikTok and in the World Religion Book Club Discord channel on Wednesday, Nov. 15, and large numbers of people — many of whom were too young to be politically active in the immediate wake of 9/11 — began praising it. “That open letter to America from Osama Bin Laden is very damning against America,” wrote one Discord user, “He was spittin facts.” “I need everyone to stop what they’re doing right now and go read ‘A Letter to America,’” TikTok user Lynette Adkins posted in a now-deleted video. “Come back here and let me know what you think. Because I feel like I’m going through like an existential crisis right now, and a lot of people are. So I just need someone else to be feeling this too.”

Although much of the nuance and tragedy of the so-called war on terror might be lost on Gen Z, points raised about aspects of U.S. foreign policy that persist today still resonate with the younger generation. “What Bin Laden was expressing in that letter are political grievances that resonate with people today: that the U.S. is unconditionally supporting the occupation of Muslim lands, that the U.S. is arming governments that are killing Muslims,” Hafez said. “I think that’s what resonated with those individuals.” Of course, while some points in the letter may be politically relevant to the current moment, it’s also a brazenly extremist and antisemitic document calling for the annihilation of the West and of the Jewish people. Yet it is being passed around TikTok, without context, like a clarion call for revolution. Indeed, its viral spread is similar to that of conspiracy theories in the wake of 9/11: “Loose Change,” the popular documentary made by three 20-somethings that argued in favor of outlandish conspiracies such as “jet fuel can’t melt steel beams” and was viewed by millions of people, has been widely regarded as the “Internet’s first blockbuster.”

Moustafa Ayad, the executive director for Africa, the Middle East and Asia at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, conducts research into how extremist groups use social media like TikTok and X (formerly Twitter) to spread their message. In his research of the Bin Laden letter’s viral moment, “we found about 41 videos that were essentially copy-paste style videos of people reading out the letter,” Mr. Ayad told New Lines. “For TikTok, those 41 videos had about 6.9 million views. But what really pushed it over the edge was on X: you had verified users posting the entire text of the speech of the letter on X, and those got tens of thousands of views. We also saw an uptick in Osama bin Laden videos — there were literally 738 million impressions on X on Osama bin Laden content just between Nov. 14 and 16.”

What’s troubling, Ayad continued, is that the success of the Bin Laden letter on social media could make it a model for extremists hoping to use networks like TikTok and X to spread their ideologies. “It provides somewhat of a blueprint for extremists or supporters of extremist groups to gain platforms,” he said. “If you can come off and just read a speech from [Islamic State group Caliph Omar Bakr] al-Baghdadi, an English translation, and try to get your friends to do that — could you make it trend based on its anti-colonial or its decolonization narrative? Its Muslim unity narrative? Is that possible? There is that sort of element to it: It provides somewhat of a blueprint on how to exploit platforms in the future, whether or not it will actually be implemented or succeed.”

This is especially problematic when it intersects with the quest for identity displayed by many recent converts. A 2021 report by the Radicalization Awareness Network, to the European Union, argued that converts’ lack of a strong basis for their religion, and a searching attitude that prioritizes meaning, identity, guidance and mental peace, can “lead them to consider radical beliefs if they are more suitable for their inner needs.” The report states that converts are often primarily guided and influenced by online documents and contacts, and that such self-study, along with the absence of links with Muslim communities or mosques, can create a risk of radicalization because of the disproportionate online presence of extremist actors.

While many are converting to Islam in the wake of the Gaza tragedy because they feel truly called, the polarized social media climate can also create an echo chamber that makes conversion more of a political statement than a religious one. “Conversion is seen in part as a kind of countercultural moment, it is seen as a defiance of authority,” Hafez said. “In the context of a social media landscape, particularly in a politicized context like this where converting to Islam becomes a political statement of solidarity with Palestinians in opposition to the dominant cultural narrative that is supportive of Israel’s policies in Gaza, that in itself could be driving the phenomenon forward. It’s a diffusion of a repertoire of resistance and defiance against the dominant culture that’s really conducive for this social media landscape.”

It’s impossible to know for sure just how widespread a phenomenon conversion has become in the wake of Oct. 7, not least because exactly how TikTok’s algorithm works remains a mystery. TikTok says the algorithm takes into account factors like likes, comments, trending sounds, hashtags and the amount of time a user spends watching videos, but how exactly the “For You” page can predict tastes so well is still largely an enigma. The algorithm has long been criticized for bias and discrimination, including racism, as well as for creating feedback loops that only ever expose users to the same kind of content they typically like and interact with. When it comes to #reverts on TikTok, that means that if you’re served a video from a convert, or even a video about the Quran or Islam, and you interact with or spend a significant amount of time watching that video, you’re more likely to see videos on the same topic in the future. If it suddenly seems like absolutely everyone on your For You page is converting to Islam, that’s the algorithm giving you what it thinks you want, which can create the sense of a mass movement happening that is not realistic outside of your TikTok app.

For his part, Ayad, who is Muslim, said that he is worried that people are becoming Muslim as a fad. “As a Muslim, I can’t be mad at people taking the shahada, but at the same time is it earnest?” he said. “I don’t know, is it a fad, is it trendy? Some of us have been living with what is essentially this idea of a stigma as being Muslim. This Muslim identity is not something we threw on. We’re born into it. That to me is the sad part.”

Both Jones and Rosario said that they believe the spate of conversions like theirs are genuine, and not just part of a larger social media trend. “I think for a lot of people who have been searching their whole lives, I think Islam really resonates with me and I would like to trust that for others that are converting it’s really resonating with them,” Jones said. “Like everything that gets big on social media I’m sure there are people who are doing it for clout but I really hope that’s not the overall trend.”

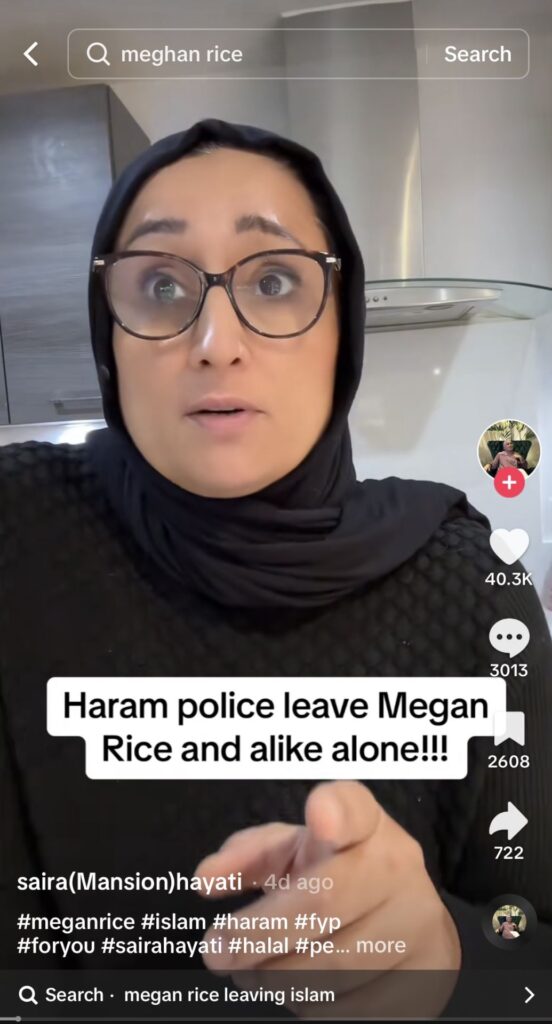

After starting the World Religion Book Club and making a name for herself on TikTok through her public study of the Quran, Rice announced suddenly last week that she would stop doing Quranic lessons on TikTok Live. Though many people had initially celebrated Rice’s conversion, others accused her of being a “fake Muslim,” or of converting to Islam just for clout and followers. Others criticized how Rice chose to worship or practice her newfound faith, accusing her of not following the religion properly, and saying her conversion wasn’t genuine. Since the backlash, Rice has said she no longer feels safe on TikTok Live, as she explained in a new video, which she captioned “#harampolice really don’t want reverts to stay in Islam! 😂 Y’all need HALP.”

“The haram police — man, are they awful,” she said, referring to ultraconservative Muslims who had begun to police her behavior online. “They’re so bad. I get like DMs and comments incessantly from people telling me, ‘You need to delete every last video on your page where you’re not wearing a hijab.’ Actually sir and ma’am, I don’t have to do a single thing you tell me to do. Those videos were before my shahada, mind your business. That’s wild to me that people do not know me personally, I do not know you personally, and you feel entitled to tell me about my life and my faith and what to do with it.”

For some, Rice’s decision to step away from the movement she helped to start, even temporarily, is a loss to the TikTok Muslim community, especially for those who see what’s happening in Gaza as a beckoning call to show solidarity with new Muslims and welcome them into the fold. As one supporter on TikTok put it: “Megan Rice is the name of this particular moment of people who have started a journey into Islam, and they do not need people who have got very narrow-minded views commenting on their posts.”

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.